Published: April 8, 2021

Summary

- Limitations of the proposed framework are discussed

- Possible ways to alleviate these limitations are also discussed

So far, we discussed the PCT framework in the spirit of a personalization tool that incorporates relevant data points to recommend cautionary behaviors to app-users.

These recommendations are intended to control the outbreak while minimizing economic disruption.

The framework is grounded in epidemiology and virology while respecting technological constraints such as user privacy and Bluetooth communication protocol.

Finally, apart from various rule-based instantiations, we also saw a deep learning solution to implement the framework.

Still, this is just the first step towards having a better contact tracing framework.

Hopefully, addressing some of the shortcomings can help us better prepare for the future.

While the subsequent post discusses why we should care, in this post, we focus on some of the limitations and possible ways to mitigate them.

- Simulator Reliability: A machine learning model relies on access to a simulator.

However, the simulator is a crude approximation of reality.

Thus, we need a way to improve the simulator to represent reality as closely as possible.

Currently, we used domain randomization to hedge against this issue to train robust deep learning models.

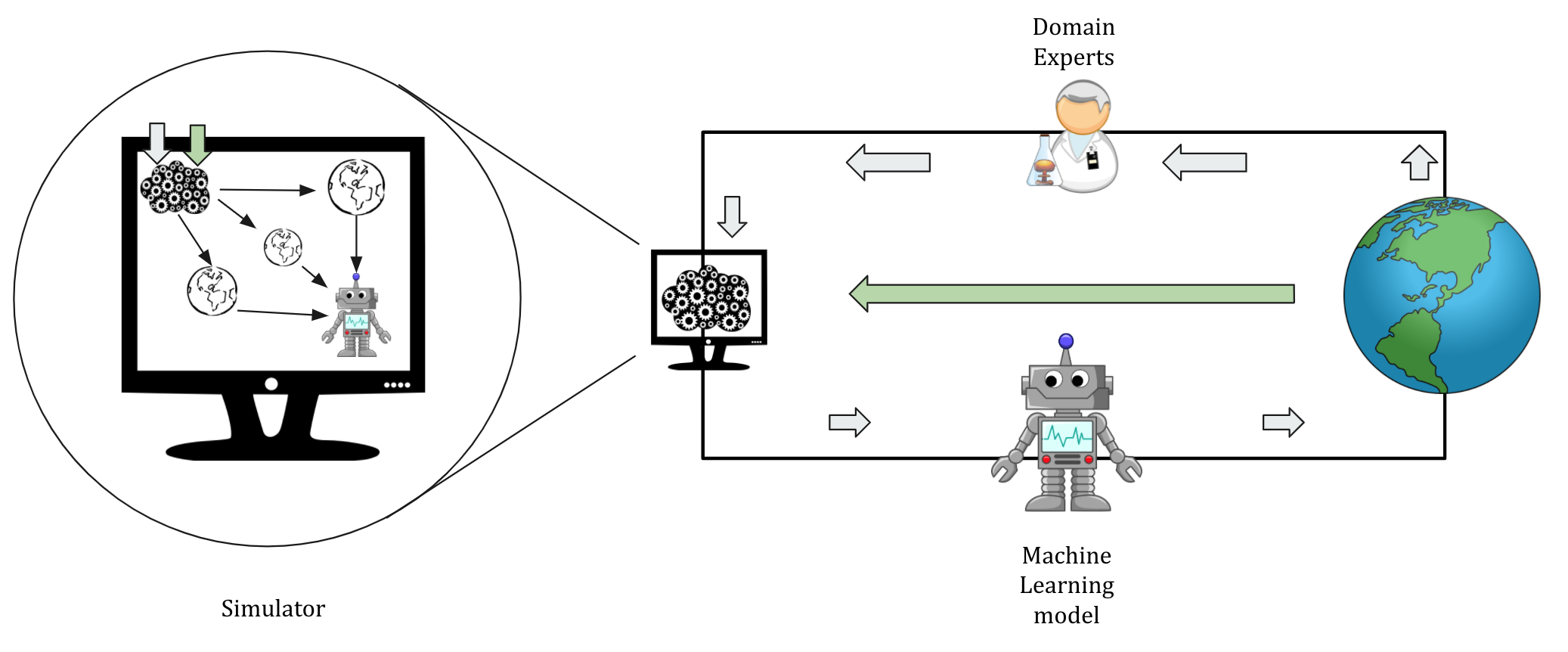

To align the simulator more closely to reality, we propose incorporating real-world app usage data (after the app is launched) along with the simulated data to improve the simulator (Figure 5).

The details are a bit involved, but the high-level idea is to parametrize the simulator (using neural networks with learnable weights) so that the differences in the simulated data and the real-world observations can tune the weights.

Figure 5: We can align the simulator to reality by using app-usage data (green arrow) with simulated data. The methods like wake-sleep algorithm and amaortized variational inference can be used here.

In doing so, we learn the simulator (generative model as neural network) and the predictor (also called inference model) in an iterative fashion.

The wake-sleep algorithm and amortized variational inference are two methods that can be employed here.

Interested readers can find more involved details of the above methods in our write-up (work of Tristan Deleu and Meng Qu), prepared while the plans to launch COVI, the app with the PCT framework, were still alive.

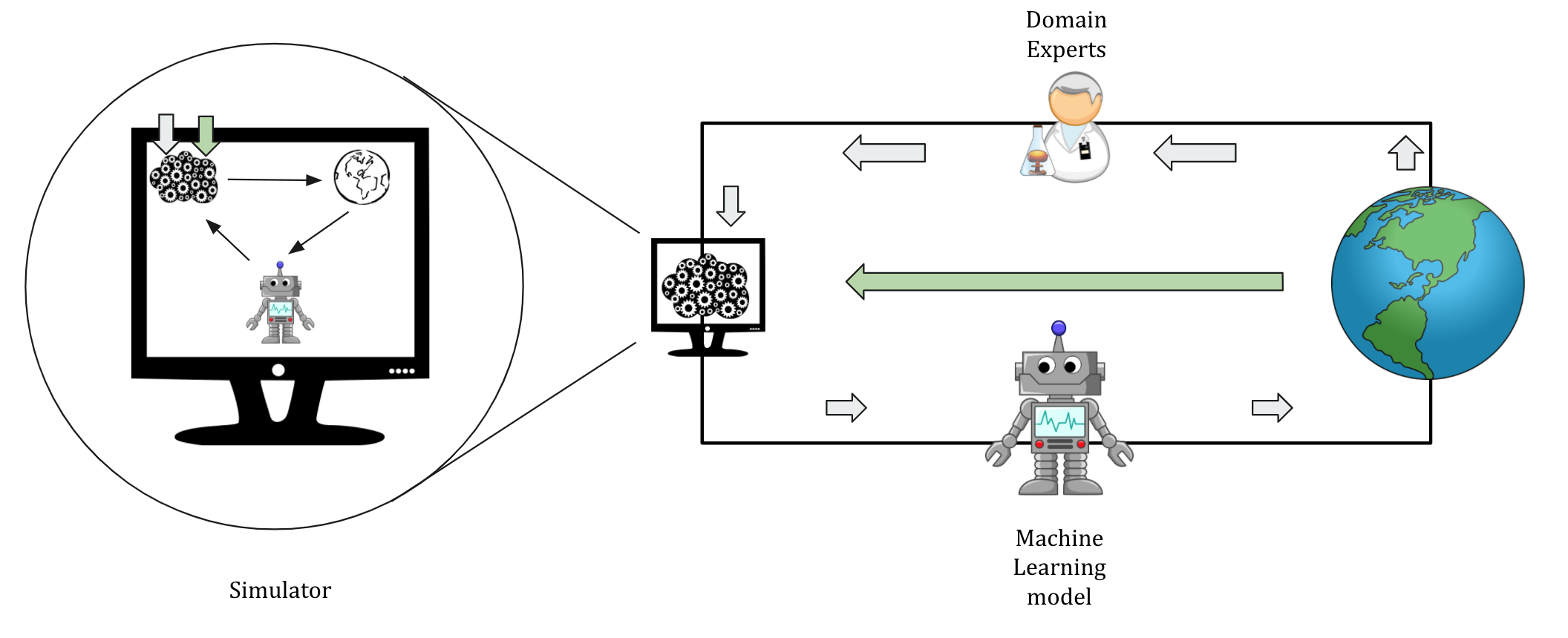

- Reinforcement Learning: We used iterative training procedure for training a deep learning model to tackle the problem of distribution shift in data.

However, the reinforcement learning (RL) paradigm is better suited to tackle this problem.

An appropriate RL formulation for predictor design can have actions as the level of behavior restrictions recommended to the app-user and rewards as carefully combined metrics of disease prevalence and mobility.

Due to RL's training requirements, we need access to a faster simulator than what we have at the moment.

Figure 6: The problem of predictor design is better suited as an RL formulation (inside the computer screen on the left). We used

iterative training for deep learning model to tackle the problem of distribution shifts. However, RL is better suited to tackle this problem.

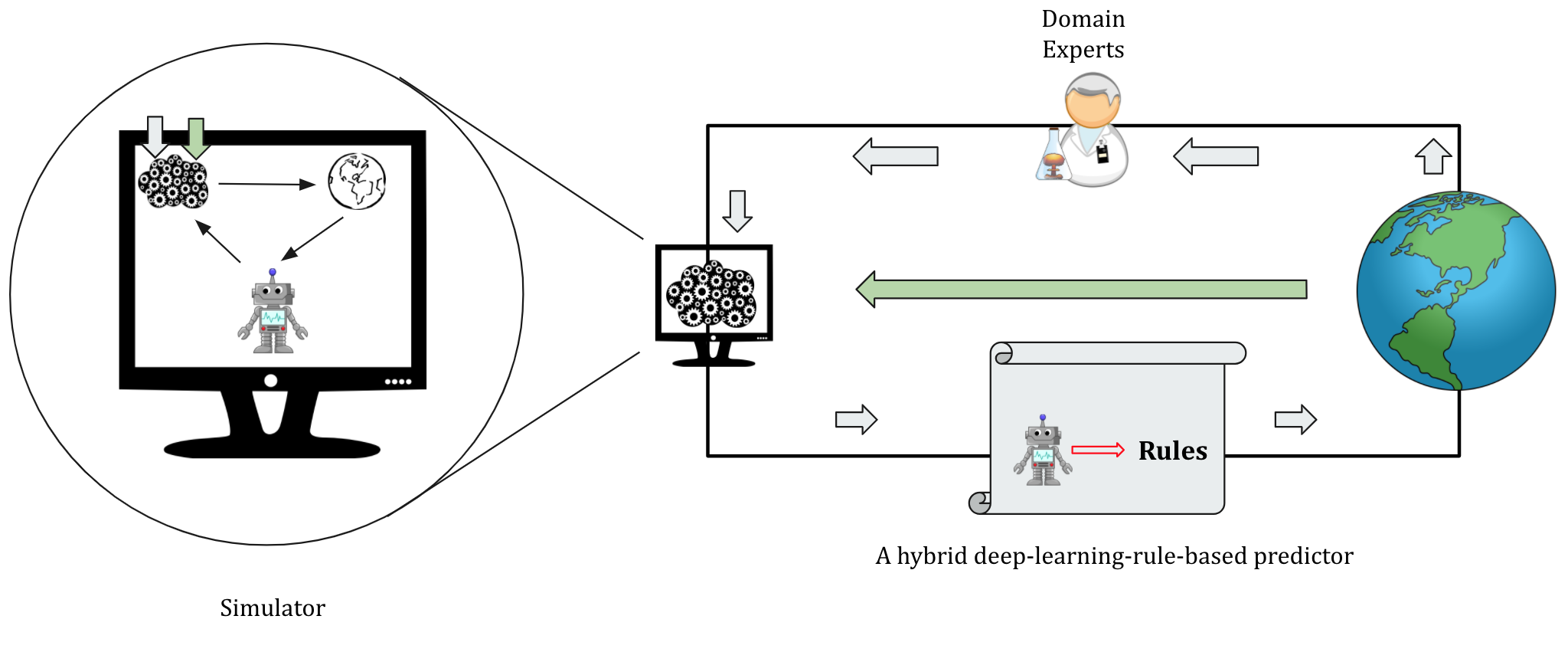

- Interpretable models: We think that for better user-adherence, we should be able to give an app-user the explanation behind the recommended behaviors.

For example, if an app-user is asked to avoid public transport, an explanation (e.g., the appearance of symptoms in the past contact) will make the app-user more likely to follow the recommendation.

The rule-based predictors are better suited to serve this purpose.

However, it is not easy to extract an explanation from the deep learning model discussed in the previous post.

To this end, apart from leveraging interpretability research being done for deep learning models, we think a hybrid approach might also be helpful.

For example, the rules can rely on the likelihood of the app-user showing symptoms or test results in the next seven days, which is an output of a learned deep learning model.

Figure 7: In addition to leveraging

interpretability research to design deep learning models capable of generating explanations, we can also opt for a hybrid predictor that has deep learning powered rules.

- Biases: As in many applied projects, addressing the sources of biases is crucial for it to perform at a scale wider than considered for prototyping.

There are various sources of bias that could creep into our plan.

To start with, assumptions built into the simulator can be biased towards team member's personal experiences.

Further, suppose we were to incorporate real-world app-usage data to improve the simulator.

In that case, data for training the predictor might become more accurate for the demographics that adopted the app compared to the new adopters from different demographics.

We would expect a thorough understanding of the sources of biases before launching an app to be aware of where it may or may not work.

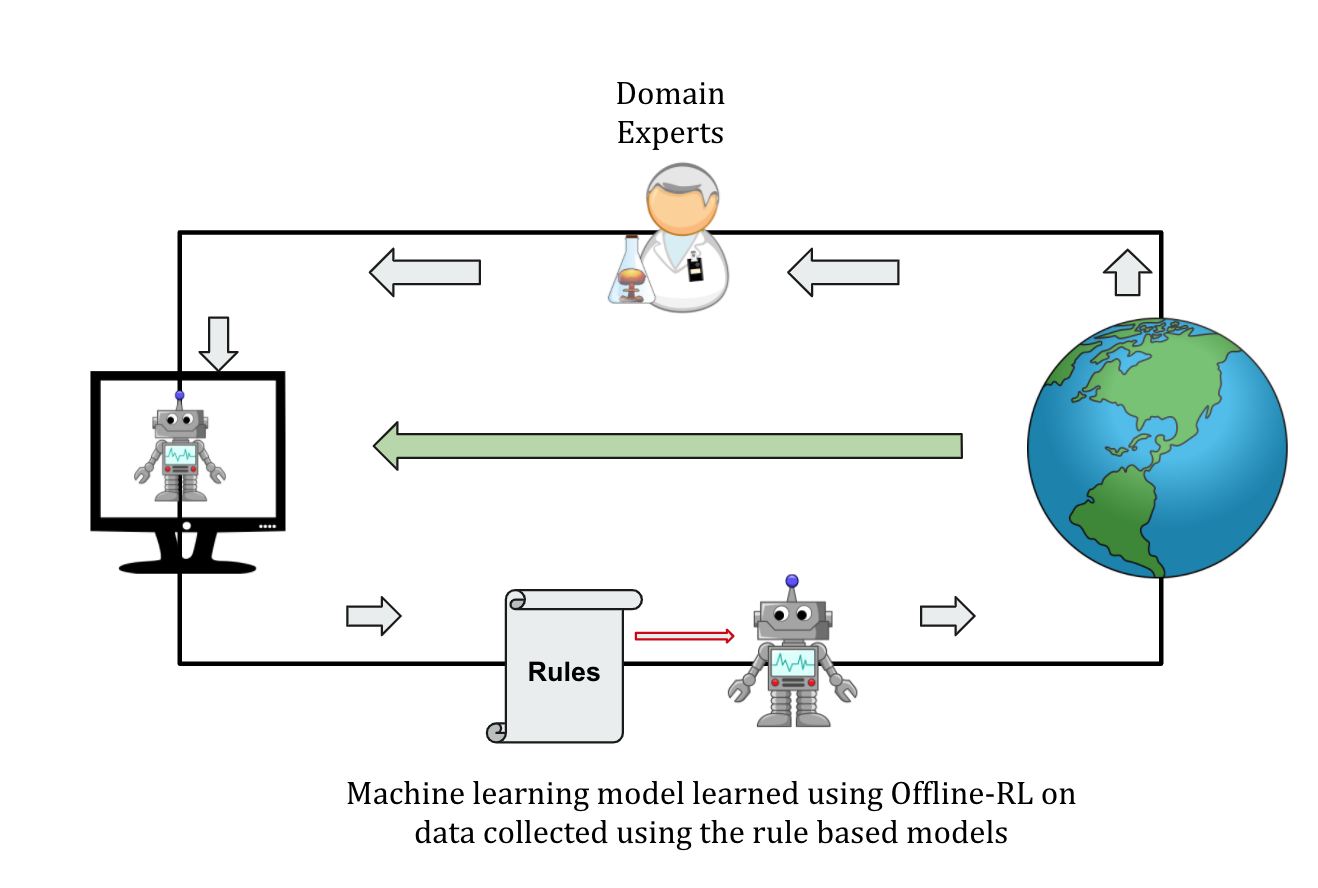

- Offline Reinforcement Learning: Building a simulator takes time.

Various assumptions that go into building a simulator might differ from one virus to another (e.g., viral load curves or mobility patterns).

Additionally, we would not have a reliable simulator until sufficient data from scientific experiments and clinical observations are collected.

In such a case, we think that the research in Offline-RL could be used to address the above problem.

The researchers have been applying it to solve problems related to autonomous driving and healthcare.

One does not have access to a high-fidelity simulator in these domains.

In our context, a roll-out of some basic rules will yield observation-reward pairs.

The objective of Offline-RL will be to learn a policy that improves upon the rolled-out policy (rule-based predictor) without trying them out on a simulator.

Figure 7: Offline-RL could potentially help when a fully reliable simulator is not available (e.g., at the very beginning of a pandemic)

There are three reasons for the above proposal.

- First, at the onset of a pandemic, when there is not much information about the virus (through clinical observations and scientific experiments) to build a reliable simulator, a conservative rule-based policy could be rapidly deployed.

This will not only help us collect initial data points but also, through Offline-RL, we will be able to improve upon the rule-based policy.

Subsequent iterations will be very much like the traditional RL.

- Second, in the absence of a scalable and fast simulator, we can hope that Offline-RL on the rule-based policy can give us a better policy with lesser iterations.

For example, a supervised framework requires three iterations of training where each iteration collects data from more than 1K simulation runs.

It takes 2-3 weeks to have a policy.

If time is a constrained resource such that only one iteration is possible, we can hope to have a better policy through Offline-RL in one iteration as compared to the supervised policy.

Note that it is cheaper to run rule-based policies as compared to neural network policies (3 hours for rule-based vs 10 hours for deep learning with 10K agents).

- Finally, a deep learning solution might not be trusted well by authorities from the very beginning.

So, it might be a useful practice to have a curriculum of deployment which gradually, and reliably, injects a smarter solution into the system.

- Backward Tracing - Covid-19 is an overdispersed phenomenon, in which a few people infect many while many infect a few.

Thus, the reproductive number for Covid-19 may not paint as bad a picture of the outbreak as it might be in reality.

For example, the reproductive number of 2 means that an infected person typically transmits the virus to two other people.

However, due to dispersion, it may be that a few people infect 10 while a lot of them infect just 1, such that there are 2 mean contagions per infected person.

Therefore, it is increasingly important to detect the source of infection as early as possible.

This is the objective of backward tracing, which differs from forward tracing (the central idea of this series) as we are interested in identifying individuals whom the source (e.g., person who reports a positive test result) might have infected.

Recall that the PCT framework relies on warning signals that encode transmitted viral load (for an encounter) in N-bits.

It serves as a proxy for the likelihood of infecting the other person involved in an encounter.

Though non-trivial, we think that reserving some bits (out of N-bits sent in a warning signal) for the likelihood of getting infected could help to identify the source of infection.

A deep learning-based solution could leverage the ground truth to get better at this prediction.

However, appropriate rules for a rule-based predictor are not clear at the moment.

- Network Optimization:

Recall that every time a predictor updates an individual's estimated viral load, it is sent across as a warning signal through a communication channel.

Such warning signal updates could heavily consume the network bandwidth while being redundant.

For example, suppose the rule-based predictor only cares about the maximum warning signal.

In that case, it might be economical to prioritize bandwidth to high-intensity warning signals while ignoring the lower ones.

Thus, not all warning signals are going to be informative.

Moreover, the prioritization of these signals may or may not depend on the predictor used for the PCT framework.

Finally, it might be helpful to include this constraint as a part of the machine learning training procedure.

We think that addressing this challenge will help us improve the framework even further.

In a similar spirit, work done by Mitra et al. addresses this problem in distributed inference setting.

- Multiple viruses:

In the event of an outbreak, unless theoretically impossible, caused by more than one virus (e.g., influenza and coronavirus) at the same time, we would want to understand how we can modify the framework.

A conservative approach would be to use the PCT framework with a viral-load profile of a "proxy-virus" with the viral load as a maximum of the two viruses.

However, one could also think of efficient use of N-bits sent through the communication channels so that the information about the type of virus and the corresponding viral load is sent.

The situation will likely test the trade-off between privacy (number of bits sent) and the framework's efficacy (controlling the outbreak while minimizing economic disruption).

Having discussed the possible limitations and corresponding ways to alleviate them, it is natural to ask if and when these improvements will help.

We discuss this in our next post.